History

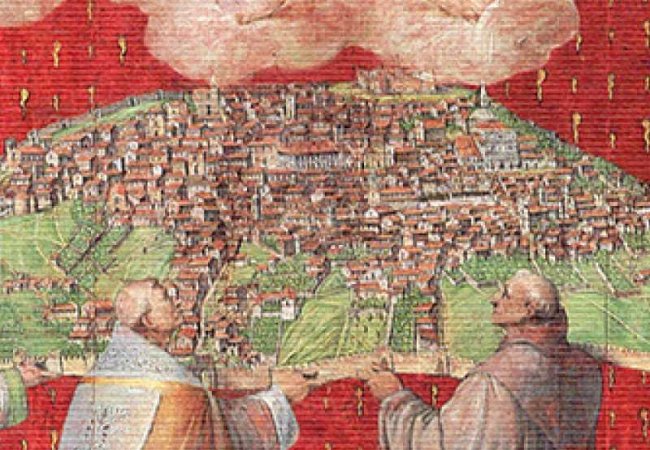

There are several churches and monuments of historic and artistic value, the heritage of its rich medieval past, such as the Fountain of the Ninety-Nine Spouts, almost a symbol of the city, the massive 16th-century Spanish castle, which crowns the city's highest point, the Basilica of St. Bernardine, (whose dome is visible above the castle's massive body in the view on the left) the greatest Renaissance church in Abruzzi, and the Church of Saint Mary in Collemaggio, the most outstanding example of Abruzzi romanesque architecture, where Peter from Morrone was crowned Pope in 1294, leaving to the city the unvaluable gift of the perdonanza.

There are various theories on the origins of the town, but documentary and architectural sources agree with the popular tradition in identifying the mid-13th century as the birth of the city. L'Aquila rose on a hill on the left bank of the Aterno river, not very far away from the ancient Roman town Amiternum, the hometown of Roman historian Sallustius, destroyed at the time of barbarian invasions, after a 1240 constitution issued by King of Sicily Frederick II Hohenstaufen, who wanted to contend the supremacy of the State of the Church in central Italy. There were already small settlements on the area, four of which - S. Giusta, S. Marciano, S. Pietro e S. Maria Paganica - , often at war with each other, decided to set aside their own differences and fulfil the decision of the king of Sicily. By 1254 L'Aquila was born, thanks to the common work of some hundreds families. In 1257 Pope Alexander VI moved there the bishopry from nearby Forcona. In 1259 the city, which had not yet been finished, sided against the anti-papal policy of Manfredi, Frederick II's son, who on the death of his father was ruling in the name of his nephew Corradino; as a consequence, Manfredi destroyed L'Aquila.

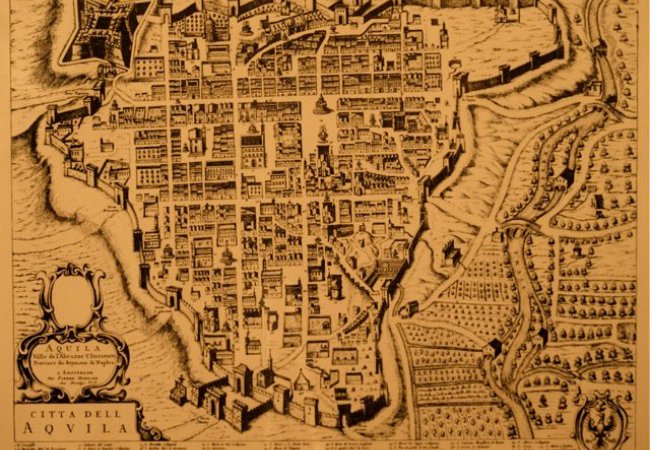

L'Aquila was abandoned for seven years until Manfredi himself was defeated and killed in a battle near Benevento (southern Italy) by Charles II of Anjou, who authorized the rebuilding of the city and order the construction of high walls all around it. Lucchisino Aleta, a Florentine aristocrat, was appointed Captain of L'Aquila by Charles of Anjou and started the construction of the massive six-foot wide, four-mile long city walls. Every now and then were placed the 86 sighting towers, which forbade enemies from entering the city. There were four doors leading into each of the four quarters of the city, which still maintain the original names: Santa Giusta, Santa Maria Paganica, San Pietro a Coppito, San Marciano.In the following centuries more doors were opened, as can be seen by the 15th-century map of the city quarters.

Each quarter had its own standard and a representation of young knights. Nowadays the ancient standards are exhibited only on very special occasions, such as the Procession of Holy Friday, when they follow the city standard. In the reconstruction the city was planned according to a well-defined land-use project which would gather within one sector each of the populations of the castles of the territory. Each castle would reproduce the native setlement with a group of houses assembled around the square and church. According to the tradition, the castles taking part to the foundation were 99, but historical researches have shown that te actual number was between 70 and 80. Each of the castles was required to build a square with a church and a fountain within the city walls, which would have given rise to the 99 churches, squares and fountains of the legend. That is also why number 99 is so important in the architecture of L'Aquila, and a very peculiar monument, the Fountain of the 99 Spouts, was given its name to celebrate the ancient origin of the town. Fontana delle 99 Cannelle.

In 1294 the city was the seat of the Conclave in which hermit Peter from Morrone was elected Pope under the name of Celestine V. After his consecration in the Church of St.Mary of Collemaggio, the annual religious rite of the pardon (Perdonanza) was established. L'Aquila soon acquired, through rebellion and warfare, a considerable degree of self-government, though nominally under the domination of Hohenstaufen, Angevin, Aragonese, and Spanish sovereigns who ruled over southern Italy and, with a population of about 60,000 inhabitants, became so powerful that it waged war on its own account, made treaties on its own authority, and from 1382 to 1556 coined its own money. During this period it was a textile center and became famous for its international trade in wool, silk, and saffron. In the aerly 15th century the city was also able to defeat the armies of Braccio da Montone, who wanted to conquer the city in order to establish his own personal kingdom in central Italy. The powerful enemy was finally defeated in a battle near Bazzano (5 km east of L'Aquila) and received a fatal wound. In 1482 a pupil of Gutenberg set up in L'Aquila one of the first printing presses in Italy.

In 1529, the army of Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire sacked L'Aquila, its territory was dismembered and its liberties revoked, and a heavy burden was imposed on it with the construction of the massive castle "ad reprimendam aquilanorum audaciam". Beginning in the 16th century the city declined in power and importance, and the decline increased after the disastrous 1703 earthquake, which, along with other earthquakes in 1315, 1349, 1452, 1501, and 1646, left a deep mark in the history and architecture of the town. In 1799 Napoleonic armies invaded the kingdom of Naples, seized all the gold and silver of the town, and dispersed the remains of Saints Celestine and Bernardine. In the XIX century the city took part to the movements for Italian Independence in 1821, 1831 and 1848, also harboring for a peiod Italian patriot Giuseppe Mazzini, who was for a time a guest in a house still extant in Via Mazzini, and, after Italian unity was achieved (1860) was plagued by brigantage, a common social disturbance of the Italian South. During World War Two the area of the railway station underwent heavy air raids by the allies, and a strong Resistance movement against the Nazi occupation arose, and had its martyrs after a bloody repression, nowadays commemorated with the monument in Piazza IX Martiri.

67100 L'Aquila (AQ) Abruzzo